Some years ago I interviewed a senior Indian bureaucrat who, as small talk, lamented the G20 and the utter waste of time it was (“all those air miles, and for what? Nothing is ever achieved”). He went on to describe how, to avoid having to be the one to sign off on any documents and decisions, he would come up with spurious reasons to pass them on to other departments, to lengthen the process a little more ultimately to avoid any blowback he might receive personally. As he spoke, the dot matrix printer whirred in the background as it churned out a page, line by line.

I’ve been thinking of that conversation this month, as events around India’s 2023 presidency of the G20 have been swinging into gear. India’s leadership is being touted as its elevation to global power status. As I read headlines trumpeting India’s desire to lean in and take charge of multilateral discourses around sometimes thorny issues, such as debt relief, digital literacy and climate change, I’ve been thinking back to experiences that suggest to me that Indian authorities are extremely skilled at process and optics, and arguably less focused on delivery and outcomes.

India’s G20 presidency undoubtedly comes at a pivotal moment, when the forces that shape and rule the world are in flux, with the geopolitical context in upheaval. India too, is a different place than before: it is now estimated to be the most populous country in the world, it is an emerging economic power, and almost certainly an emerged political one in the global order.

India’s outward economic story is sound: the growth outlook for this financial year is 6.1 per cent, according to the International Monetary Fund. But internally, there’s a more nuanced story, with unemployment at a 16-month high of 8.3 per cent, and ongoing air quality woes, with polluted skies now plaguing coastal Mumbai.

Despite the mixed bag, India has ploughed ahead with giving its G20 year its absolute all. For a country where economists get rock star treatment, it’s fitting that India seems to be approaching its G20 hosting duties like it’s Eurovision (everyone’s favourite multilat).

There are more than 50 meetings running from February to May, and in total around 200 are expected to be held, covering 30 workstreams. Gatherings are being held all over India: from the Rann of Kutch, where delegates were recently videoed doing early-morning yoga in the salt plains, to Darjeeling, to Goa. Foreign ministers from G20 countries will gather in Delhi on 1–2 March, and finance ministers and central bank governors are due to meet in April – in Washington DC, sadly, where daybreak yoga would be a little less atmospheric. There are working groups on tourism, environment and climate change, agriculture, digital economy, health, financial inclusion and more.

India has articulated some bold goals: to broker international consensus on security, health resilience, food security and inclusive growth. It has also highlighted some areas where it would like to see progress made, such as debt relief for developing nations.

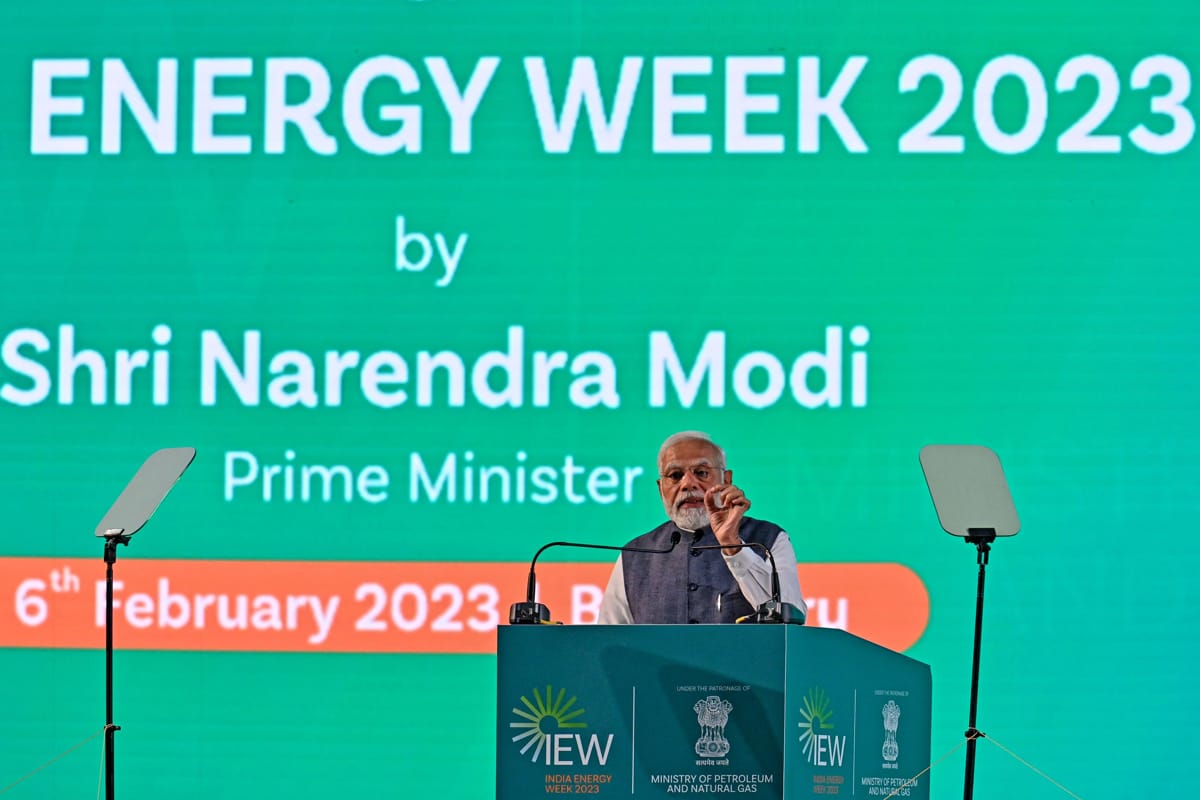

All this comes with the backdrop of India’s current role in the world. India is transcending the limitations of its developing status to become a major trade partner and global power, one that is confident in its ability to command respect, even from its former colonial rulers. This G20 presidency shows that there is a level of trust in the country to be able to deliver. This symbolic importance of the job has not been lost on the government, which hopes to harness goodwill off the back of it towards electoral gains ahead of a general election due in 2024. A successful stint that sees India lauded worldwide for its hosting could help bolster Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s prospects for re-election.

Does India’s G20 year have any chance of achieving its goals? The mood is certainly ripe for a refocus on the developing world, and equipping it with the resources and solutions needed to try to offset the impacts of climate change and global conflict, which have disproportionately impacted economically poorer regions. But India’s internal realities don’t always reflect the stories it likes to tell the world about itself.

For example, development indicators remain stubbornly low. India last year ranked 132 out of 191 countries on the United Nations Human Development Index, and performed worse than its neighbour Bangladesh in many areas. While the UN has lauded India’s efforts to narrow the gender development gap, women’s workforce participation is declining, at 19 per cent in 2021, compared with 32 percent in 2005. When it comes to digital access, figures show a digital divide, with only 43 per cent of Indians having access to the internet, and more of them men than women.

There isn’t a lot of incisive commentary in the Indian media about what the country can realistically achieve in its G20 year. Instead, there are headlines like “Why India is a leader among digital democracies” and “Under India’s leadership, G20 can solve impending global healthcare crisis”. Confidence in India’s ability to deliver results is healthy, to say the least.

More than 200 meetings with scores of delegates from around the world flying in to attend is, as my bureaucrat interviewee pointed out, a lot of air miles. Will it be worth it? The G20 could be an opportunity to solve some pressing global issues, and certainly debt relief, equitable health access and food security have a rightful place at the top of the list. But whether India’s year as G20 president is more than a platform to showcase its homegrown exceptionalism and hubris to the world, is yet to be seen. India will need to produce more than headlines if it is going to achieve the goals it has set for itself.