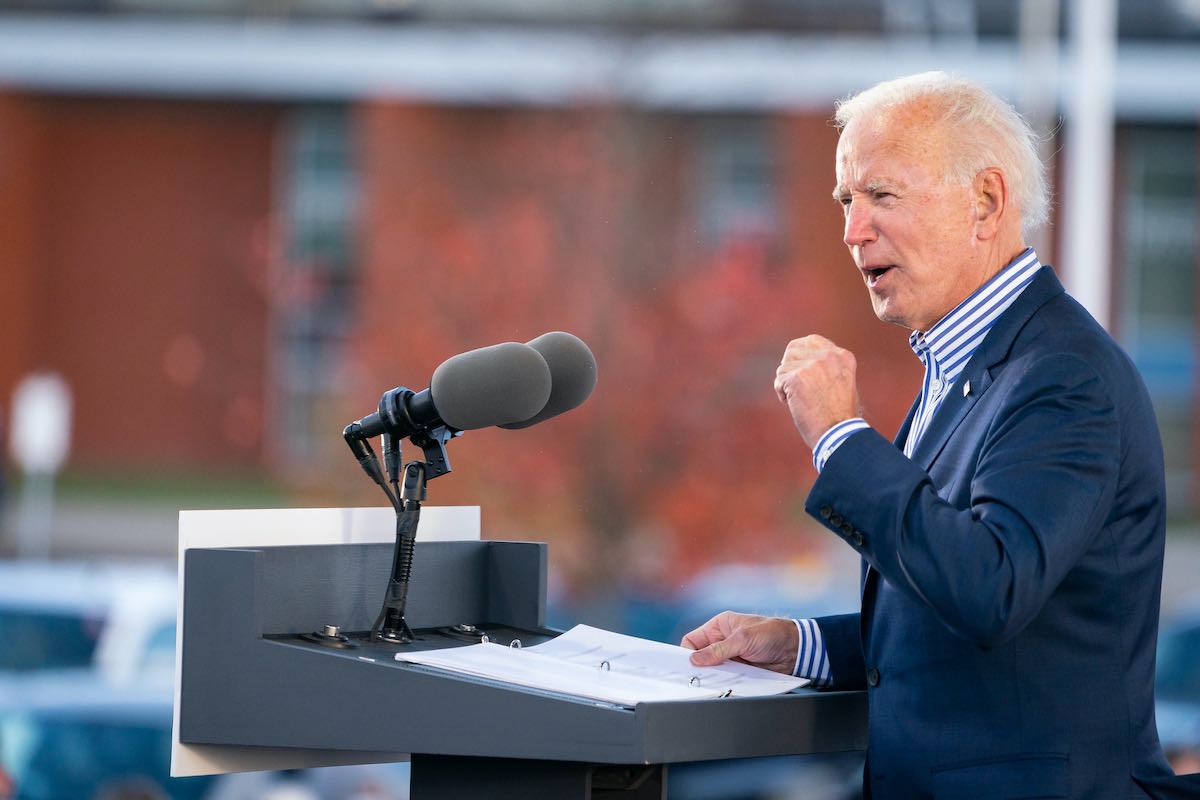

US President-elect Joe Biden’s decision to select retired Army General Lloyd Austin to be his Secretary of Defense triggered a somewhat predictable set of hot takes among US academics and commentators. Aside from questions about what his appointment would mean for civil-military relations, a major point of criticism was that Austin had little professional experience in Asia, at a time when the United States’ primarily military challenge is emanating from China. Biden’s initial defense of his decision did little to allay concerns, and Austin felt compelled to address the criticism directly:

I understand the important role of the Department of Defense and the role that it plays in maintaining stability and deterring aggression and defending and supporting crucial alliances around the world, including in the Asia-Pacific, in Europe, and around the world.

Meanwhile, other observers shot back that Asian security policy should not be the top US government priority in the midst of a raging pandemic and that the United States should not be deferring to the preferences of Asian elites.

The constant searching for clues about how much emphasis the US government is going to place on China, Asia or the Indo-Pacific based on personnel and rhetoric is unlikely to abate soon. Obviously, the selection of key individuals matters, and the adoption of certain language can send important signals.

But the narrow debate on Asia policy, as currently framed, obscures some important realities. There is no uniform opinion in Asia (or the Indo-Pacific) about what US regional policy should look like. While acknowledging the diversity of opinions within various capitals, three broad strains are emerging.

The first is among certain US allies and partners who believe a US military presence in the region is, on the whole, reassuring. This view – broadly shared by the current leaderships in Japan, Australia and India – has started to assume a number of cardinal features. One is an appreciation that there are certain security functions – such as freedom of navigation operations and other forms of power projection – that only the United States is able to fulfil on a regular, sustained basis. The United States’ relinquishment of such a role would leave a gaping void, with consequences for the balance of power.

In hindsight, it took the administrations of Bush, Obama and Trump roughly four years, six years, and nine months, respectively, to reach much the same conclusion: that relations with China would be more structurally competitive than previously imagined.

At the same time, there is growing realism that the United States cannot be expected to bear the burden for regional security entirely on its own. This will require others to step up their regional security presence. The shifting rhetoric and scope of these countries’ military operations reflect this, even if such actions have not always been matched with sufficient resource allocations.

Additionally, security and economic dependence are linked. Consequently, these countries have taken discrete steps to coordinate on supply-chain resilience and ensure technological autonomy from China on national security grounds.

A second view, prevalent among many leaders in Southeast Asia, represents a high level of comfort with the old status quo, whereby the United States could continue to underwrite regional security while enabling the region to enjoy a high level of economic interdependence with China. From their standpoint, such an arrangement represented the best of both worlds, and they retain remarkable faith (despite evidence to the contrary) in the ability of Beijing and Washington to revert to prior arrangements.

Such views often get disproportionate attention in Washington due to the belief that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) forms the primary institutional foundation for the broader region. Indeed, former officials of certain ASEAN member states are sometimes audacious enough to presume to speak on behalf of all Asia.

A third view, of course, is that of the leadership in China. Beijing is now openly dangling the possibility of a reset in relations with the United States under a Biden administration, with renewed talk of a “new type of great power relations.” In addition to urging Washington to abandon the logic and terminology of a free and open Indo-Pacific, Chinese experts and commentators have suggested that Biden pursue a more “pragmatic” policy towards their country.

Simply put, officials and experts in Beijing are actively urging a more accommodating approach by Washington to Chinese assertiveness, while warning that economic decoupling would be self-defeating. The incoming Biden administration will face an immediate choice as to whether to acknowledge or reject these propositions. In particular, the belief that the United States needs to cooperate with China on issues such as climate change deserves scrutiny; Beijing is not pursuing aggressive climate targets out of any special favor to Washington.

It often goes overlooked in the ongoing debates on US Asia policy that positions change personnel as much as the other way around. Austin, according to some critics, is not the obvious candidate for a Cabinet berth in an era of great-power competition. But neither were H.R. McMaster, James Mattis, Rex Tillerson or Mike Pompeo, the principals under whom the 2017 National Security Strategy, 2018 National Defence Strategy and Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy were formulated.

As the experience of the past three presidencies shows, US Asia policy often undergoes shifts during an administration’s tenure. It is instructive to look at what happened in each of these cases: Under George W. Bush, the priority accorded the Global War on Terror and the Six Party Talks with North Korea initially overshadowed competition with China. It was only in Bush’s second term that the emphasis shifted, leading to intensified security cooperation with the region.

Barack Obama assumed office with a preference for “strategic reassurance” with China. But frustrated by a lack of progress, his administration announced a “pivot” or “rebalance” to Asia two years later. In Obama’s second term, the security dimensions of the pivot were initially watered down and engagement with China was once again prioritised. It was only after 2014 that more competitive defence and trade arrangements were considered, although some might argue too little and too late to have made a difference, as in the South China Sea.

Finally, Trump entered office with the idea of working with Xi Jinping, resulting in the Mar-a-Lago summit. It was only after October 2017 that his administration began to reverse course, resulting in a shift in both tone and policy.

In hindsight, it took the administrations of Bush, Obama and Trump roughly four years, six years, and nine months, respectively, to reach much the same conclusion: that relations with China would be more structurally competitive than previously imagined. It will take some time before a Biden administration can fill senior positions, make the necessary assessments and embark upon regional engagement.

The primary yardstick by which the new administration’s approach to the Indo-Pacific should be assessed ought not to be the appointment of personnel or use of specific phrases, but rather how long it takes to adopt a sound basis for regional policy and how quickly it is able to accelerate the learning curve.