Celebrity sells – it always has. But in the digital age, the boundaries of celebrity have changed. Once it was the prerogative of movie, sports or music stars to front a fashion label or promote perfume. But nowadays the marketplace is saturated with any number of online lifestyle and wellness “influencers”, social media users who by virtue of their taste, niche expertise or marketing savvy develop audiences of thousands – sometimes millions – who seek to emulate their lifestyle.

And promoting products is only the beginning. Such influencers can have a profound effect in imparting attitudes and beliefs, too.

Most of the time, this is harmless, a new thread in the media milieu. Yet at a time of pandemic, where medical advice is heavily contested and conspiracy theories from the dark reaches of the internet have proliferated, some online lifestyle influencers are amplifying misinformation and disinformation.

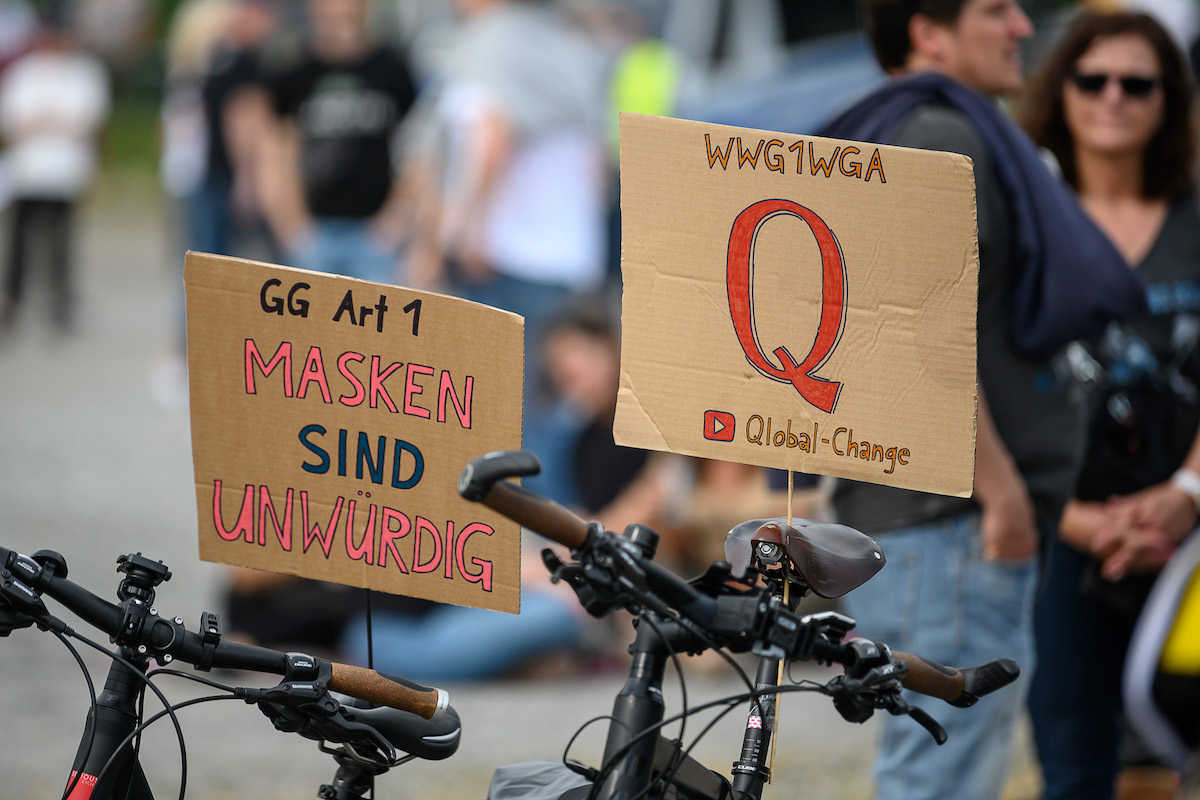

In a new twist during the Covid-19 crisis, three formerly distinct online ecosystems – those occupied by lifestyle/wellness influencers, “QAnon” conspiracy believers, and violent extremists – have in some instances become intertwined, through shared conspiracy-related hashtags and wild claims about the dangers of vaccines, 5G and the evils of the “deep state”.

QAnon is not only a conspiracy movement. It has also been deemed a domestic terror threat by the FBI.

Numerous recent studies and news reports have shown that extremist groups are exploiting the Covid-19 pandemic in an attempt to justify their narratives, recruit followers or incite violence. Extremist narratives have always contained strong conspiratorial elements, and this time is no different. Coronavirus-related conspiracies are deftly interwoven through extremist narratives and mobilisation efforts.

But the connection with online lifestyle and wellness influencers marks a change. This crossover came about after some online lifestyle and wellness influencers became entrepreneurs of conspiracy theories, using them to boost their profiles and to promote and validate their views of wellness. One of the more dangerous conspiracies promoted by lifestyle/wellness influencers are QAnon conspiracies.

The QAnon movement has its origins in the so-called “pizzagate” conspiracy of 2016. In its current form, QAnon alleges that there is a US government insider with a “Q-level clearance” who is communicating cryptically with his followers online. QAnon followers believe there is a “deep state” within the US government that is controlled by a cabal of Democrats and liberal Hollywood celebrities who are also Satan-worshiping paedophiles. Through Q, President Donald Trump was manifested to expose and shut down these ritualistic paedophile rings. During the Covid-19 pandemic, QAnon conspiracy groups and posts have also promoted the idea that the pandemic was, alternately, another deep-state plot, a hoax, and a Chinese bio-weapon, among other health disinformation.

However, QAnon is not only a conspiracy movement. It has also been deemed a domestic terror threat by the FBI. A leaked FBI memo written in May 2019 assessed QAnon believers as “conspiracy-driven domestic extremists” and that QAnon and other crowd sourced conspiracies would “very likely motivate some domestic extremists to commit criminal and sometimes violent activity”.

The memo cited two violent incidents linked to QAnon, but there have been at least three other violent incidents since its publication, with researchers also examining its spread beyond the United States. What started as a US-based pro-Trump conspiracy movement has now gone global and includes a number of proponents in Australia, reportedly including a family friend of the Prime Minister with a substantial social media following.

A recent article by Insider magazine highlighted a number of lifestyle influencers who were posting QAnon conspiracies related to the pandemic. Outlets such as Buzzfeed, Mother Jones and Huffington Post have also revealed a string of other popular lifestyle, design and wellness influencers who have become vectors of Covid-19 and QAnon conspiracies. Some have latched onto the discredited “plandemic” film released in May or QAnon memes, variously claiming the coronavirus is fake, or that the deep state is responsible for spreading the virus, or that pandemic lockdown measures are a tool of oppression. Still others have encouraged followers to attend anti-lockdown protests which have included a number of far-right extremists in their midst.

Ironically, one of the most widely shared erroneous memes about the virus being spread by people in China eating bat soup, which was created and circulated by conspiracy theorists and extremists alike, was itself appropriated from a Chinese online influencer and celebrity vlogger, who said that a video of her eating a local delicacy of bat soup in Palau for her vlog was “hijacked by accounts fanning out malicious panic”.

By promoting conspiracies or “alternative” information in the name of wellness and alternative lifestyles, the online influencers of today can serve, however unwittingly, as a gateway directing users to further, darker corners of the internet.

The intersection between wellness and violent conspiracies seems unexpected, but the wellness movement has its origins in anti-establishment and anti-mainstream medical circles. Scholars such as Charlotte Ward and David Vaos have examined the confluence of new age wellness and conspiracy, which they termed “conspirituality”, an intersection between new age wellness, belief in the dangers of a “new world order” and big pharma, and a shared emphasis on “awakening” and revealing truths.

Until recently, the convergence of wellness and conspiracy in a drive for awakening and societal change emphasised the non-violent and the peaceful. However, the emergence of the QAnon movement has pushed things in a more troubling direction.

The online links between far right, QAnon conspiracy groups and some online wellness and lifestyle influencers have grown during the pandemic, the ensuing lockdown and response to restrictions. Online wellness and lifestyle influencers who peddle QAnon conspiracy theories about the pandemic can potentially drive traffic to online extremist groups through shared QAnon related hashtags such as #QAnon, #TheGreatAwakening, #Plandemic, #GermJihad, #MAGA, #whitegenocide #WWG1WGA or #coronavirushoax. This can also be done when influencers have used memes and iconography also appropriated by right-wing extremists – for example “red pill blue pill”, “falling down the rabbit hole”, or “where we go one we go all”.

More analysis is needed, but there is emerging evidence to suggest that online influencers’ posts related to QAnon are being cross-posted and referenced by extremists groups on online forums. And by promoting conspiracies or “alternative” information in the name of wellness and alternative lifestyles, the online influencers of today can serve, however unwittingly, as a gateway directing users to further, darker corners of the internet.

Social media lifestyle influencers posting about QAnon not only serve to normalise this fringe movement, but can potentially undermine efforts by internet companies to “de-platform” purveyors of disinformation, label misleading posts and weed out prohibited content (as identified in their terms of service). Internet companies such as Reddit have banned QAnon forums for inciting violence. Facebook has banned a number of QAnon pages for inauthentic behaviour ,and Apple has removed a QAnon app from its store. Twitter recently announced it is suspending thousands of QAnon accounts. But QAnon posts still flourish online.

Because lifestyle and wellness influencers generate substantial revenue, have helped build social media businesses, and have not generally intersected with extremist movements before, there is a danger that influencers will escape extremist content reporting and moderation. Furthermore, influencer posts are likely to reach a wider audience than extremist group posts as they are less scrutinised by social media mechanisms monitoring extremist content.

Lifestyle and wellness influencers are particularly challenging because, as numerous surveys have found, influencer marketing has exploded. More and more people are turning to influencers and online personalities for inspiration, recommendations and purchasing advise. Online influencers who’ve latched onto QAnon present conspiracies in an engaging, appealing and relatable manner, often interspersing posts promoting QAnon among stylised photos of fashion, workouts and recipes. The same skills that these influencers use for consumer brand marketing have helped turn an outlandish conspiracy theory into an “acceptable option in the market place of ideas”.

A expanded version of this article is available at Global Network on Extremism and Technology of which the Lowy Institute is a core partner. This article is part of a year long series examining extremism and technology.