It is likely that the isolationist trend in global politics will be strengthened after Covid-19. For many policymakers – and a large section of global public opinion – the vulnerability of international supply lines for medical equipment and pharmaceuticals seemingly points to only one inevitable conclusion: the need for countries to enhance their self-sufficiency.

Yet it is important that in the post-Covid-19 world we remember where globalisation succeeded as well as where it failed. The science behind the pandemic response suggests this crisis will be solved by strength in numbers, not countries going it alone.

Far away from the contested high politics of the World Health Organization (WHO) there exists a beehive of global technical activity. Specialists are networking with their counterparts across the world in a race against time.

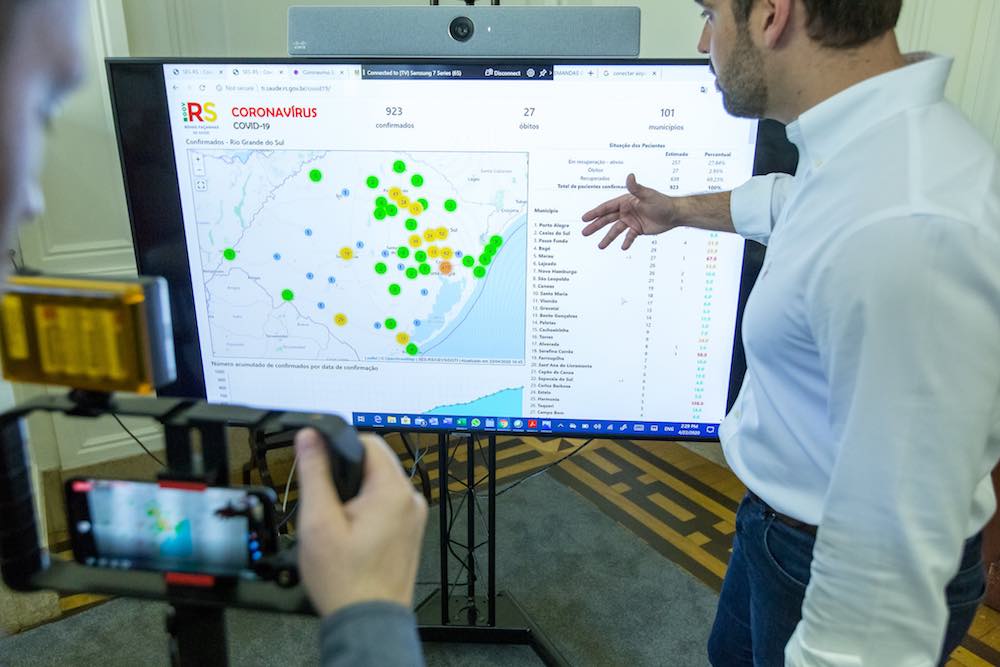

On 31 December, a case of pneumonia with an unknown cause was reported to the WHO office in China. Ten days later the genetic sequence for the “2019 novel coronavirus” was deposited on GenBank, a publicly accessible genetic sequence database by a team of researchers from China and Australia. This novel coronavirus would later become known as Covid-19. Only two weeks after its sequence was made public, a lab in Berlin published details of a test and workflow so scientists could begin detecting the virus in patients.

The solution to the virus when it comes in the form of a breakthrough vaccine will be an astonishing feat of hard-headed, no-nonsense cross-border cooperation.

This is markedly different from past experience. For instance, it took almost six months to identify the virus responsible for the 2002–2003 SARS outbreak.

Such breakthroughs in technical collaboration by government agencies, research institutes and scientists operating in different jurisdictions highlight the strengths of an interconnected world and defies the anti-globalist narrative.

Formal and informal research links will be critical to bringing the pandemic to an end. And none more so than in what should become an increasingly familiar field, that of bioinformatics, which has been at the core of the scientific community’s Covid-19 response.

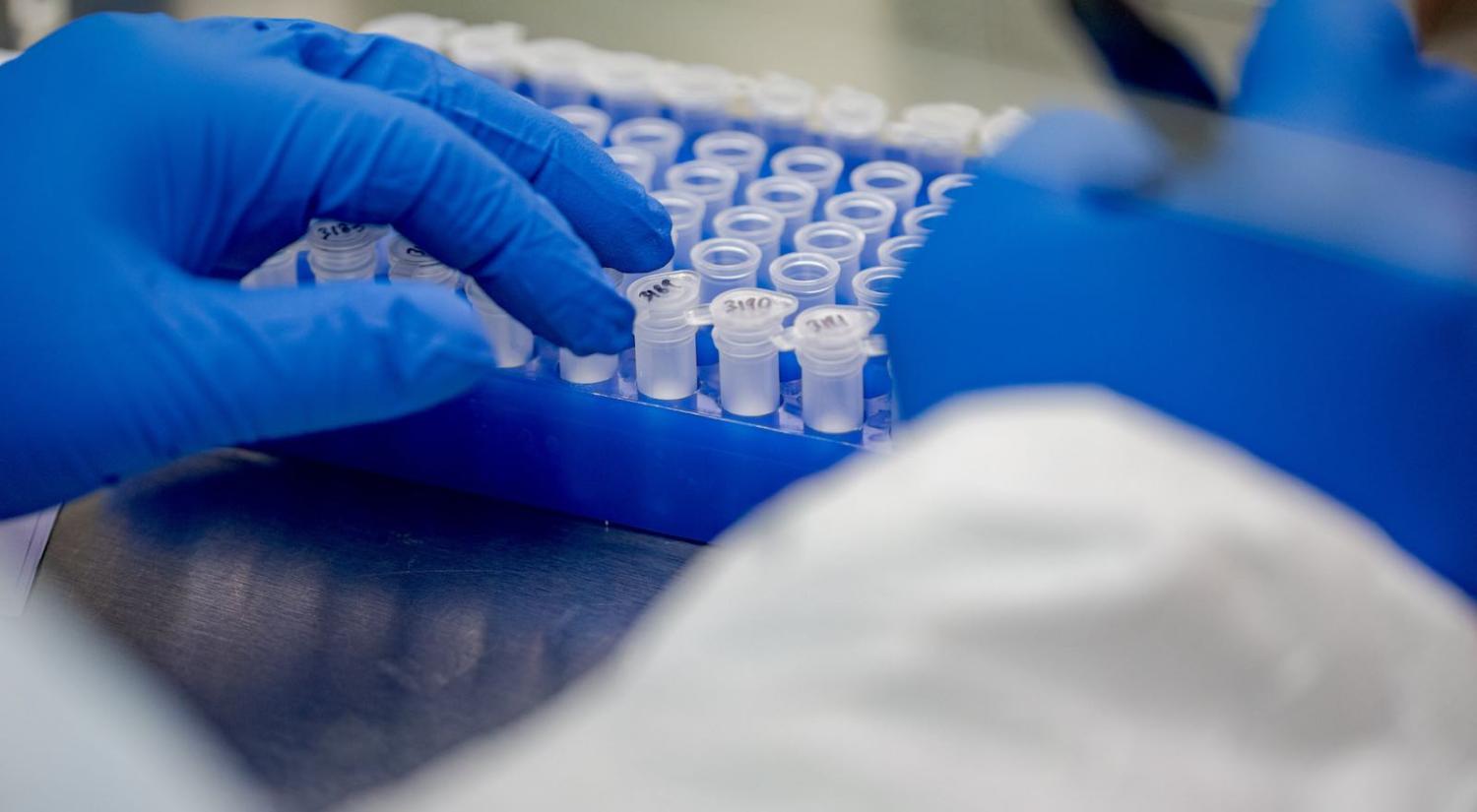

Bioinformatics is the science of managing and analysing biological information stored in digital databases. It is one of the fastest growing fields in biology, with the adoption of automated laboratory equipment and digital analysis tools becoming more frequent since the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003.

Bioinformatics is what allows labs to simultaneously collaborate on Covid-19 research no matter where they are located. In response to the virus, many bioinformatics institutes and companies have implemented dedicated platforms for Covid-19 information exchange. Crucially, the WHO has instituted a data sharing protocol through its online bulletin, which ensures that all research manuscripts relevant to the pandemic will be freely available.

The European Molecular Biology Laboratory has also created a Covid-19 portal that collates reference data and specialist datasets from biological institutes across Europe on one public platform.

Even the private sector has gotten in on the act. Benchling, an American company that provides digital lab tools such as sequence and workflow design tools, is providing all its Covid-19 resources for free. This includes experimental protocols for the detection of the virus as published by the University of California, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Mammoth Biosciences.

There are also grassroots initiatives within the scientific community, such as “Crowdfight COVID-19”, a platform that links volunteer scientists to tasks requested by Covid-19 researchers. Such tasks include requests for data input, data analysis or the procurement of specialised reagents for use in chemical analysis. Some 40,000 volunteers have signed up to the service since its inception in early March.

The same strength in numbers approach to scientific collaboration is being used elsewhere to secure the supply of life-saving ventilators and other medical equipment to treat coronavirus.

Despite the European Union’s initial and much publicised failings to recognise the scale of the Covid-19 threat and act jointly to mitigate it, the European Commission is now showing how collective action can help resource governments through the health crisis. The Commission has created a “Joint European Procurement Initiative”, which has been able to secure the supply of critical medical supplies for its 27 member states. The initiative was able procure equipment within two weeks of its creation despite a global shortage. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom, which was invited to join but declined to participate in the initiative, is facing critical delays in the supply of medical gear for front-line health workers.

The rapid progress to date of the scientific community and the initiatives taken in Europe showcase that this global health crisis has not reduced international solidarity to empty political rhetoric. To the contrary, the solution to the virus when it comes in the form of a breakthrough vaccine will be an astonishing feat of hard-headed, no-nonsense cross-border cooperation.