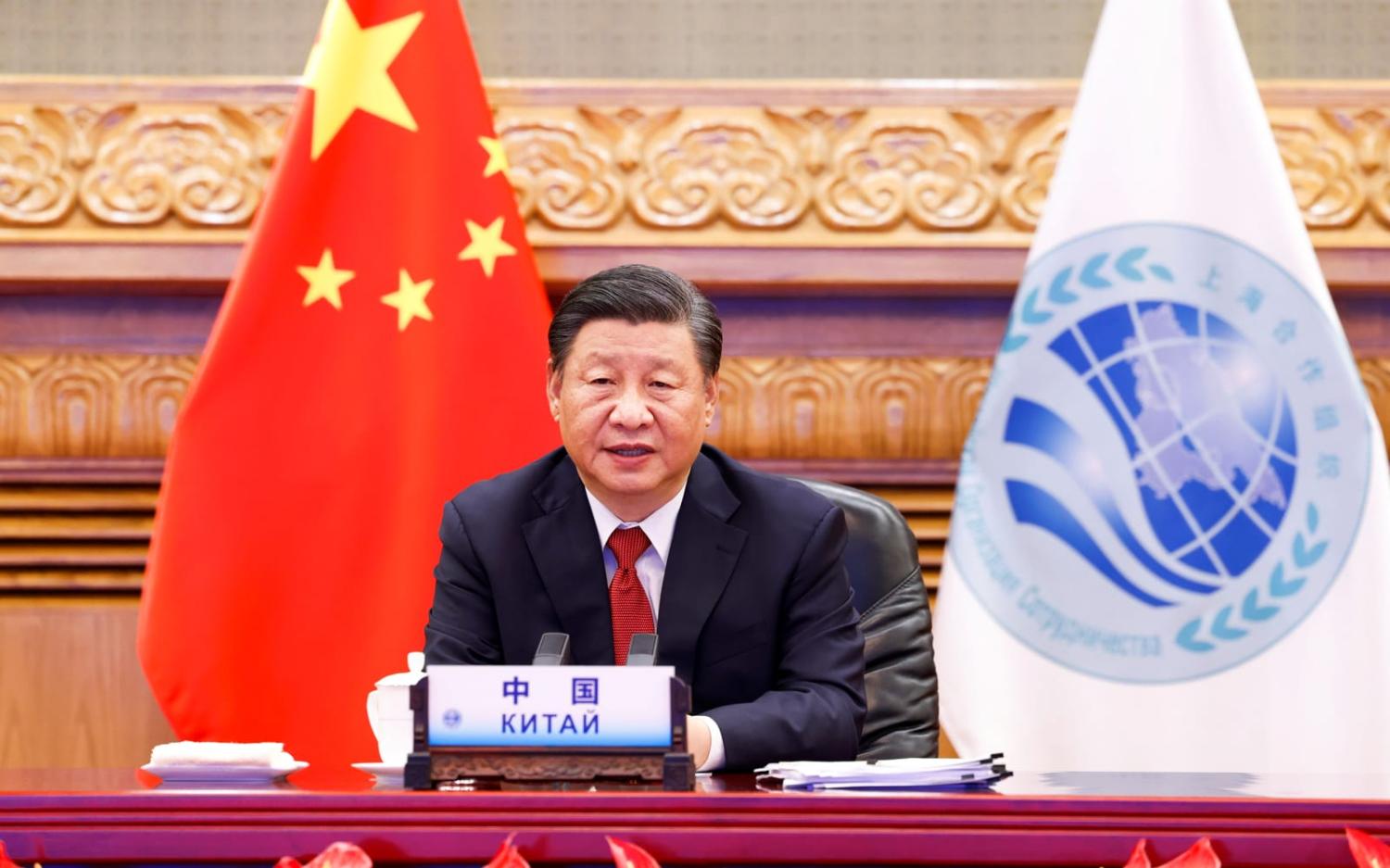

The 22nd leaders’ summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, to be held on 15–16 September, will be the first in-person gathering of the central Asian grouping since 2019. The world’s eyes will be on the ancient Uzbek Silk Road city Samarkand as the host because this summit will likely provide Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin their first face-to-face meeting since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and declaration last year of a “forever partnership”.

It also appears likely that India’s PM Narendra Modi will participate. Modi is expected to have meetings with Putin and Xi, giving a further glimpse as to how India is likely to map out its relationship with Eurasia’s great powers.

And, of course, the meeting will also be notable as it will be part of the Chinese leader’s first foray abroad since January 2020.

The Covid-19 interruptions and the Ukraine invasion have understandably magnified attention on a grouping that is regularly ignored by those outside Central Asia. But the downplaying of the SCO in the past reflected not just a tendency of Western scholars and analysts to gloss over Asia’s continental heartland but also to see the organisation as something of an empty multilateral vessel.

Yet since its creation in June 2001, the SCO has performed an important role in the geopolitics of the world’s biggest and most crucial continent. It was first established by the People’s Republic of China as a geopolitical stabilisation mechanism in its West Asian borderlands – a zone that had developed a sense of endemic instability in the 1990s. From the outset, the SCO presented itself as a bulwark against “terrorism, separatism and extremism”, a language that sought to capitalise on the global counter-terrorist consensus of the 9/11 era, as well as reflecting real concerns in Beijing about threats to Chinese Communist Party power.

As the SCO has evolved, it has focused not only on counter-terrorism but also on drug trafficking, military cooperation and dabbled with economic collaboration. In many respects it was an illustrative example of the ways in which Asia’s states turned to multilateral security mechanisms in the 1990s and early 2000s as they began to grapple with the security consequences of globalisation and the unsettling of the old strategic balance.

While the SCO has, formally, a broad agenda, its security and geopolitical dimensions have begun to grow in significance. Early on, the focus was aimed at reducing American influence in the region that had become significant due to the sustained engagement in Afghanistan. More recently, it has been energised by the growing alignment of Russian and Chinese interests as well as the increased significance of Central Asia. The founding members were China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. India and Pakistan joined in 2017, reflecting the priority that the two South Asian states placed on the Asian landmass and their recognition of its growing weight.

The 2022 summit will mark Iran’s accession to the group, a move that underscores its distinctive geopolitical outlook. More broadly, Mongolia, Afghanistan and Belarus have observer status, while Sri Lanka, Turkey, Cambodia, Azerbaijan, Nepal and Armenia are dialogue partners, to be joined by Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Egypt in the upcoming meeting.

This leaves the SCO now among the world’s largest regional organisations with its members accounting for around one-third of global GDP, about 40 per cent of the world’s population, and nearly two-thirds of the Eurasian landmass.

The 2022 summit is a timely reminder of just how important this zone has become, how substantial the membership is, and how far this grouping is from being aligned with what might be described as a status quo geopolitical and ideological orientation to the global order. Apart from India, none of the members is a liberal democracy, and the Modi government has proven to be decidedly relaxed about the erosion of core liberal principles if they serve its political interests.

The Ukraine invasion will cast a significant shadow on the meeting. Kazakhstan has, somewhat surprisingly, supported Ukraine, while China and India have to varying degrees supported or at least not publicly opposed Russia’s attacks. The summit will provide some sense as to the positions of the members in relation to a conflict that is increasingly seen as a contest between a liberal democratic conception of the international order and an authoritarian one.

For the Quad members, the SCO makes for slightly uncomfortable viewing. Most obviously India, a crucial member in the four-party grouping, is showing a willingness to play a much more autonomous hand in the larger geopolitical game in the region. Also, the SCO has displayed a much greater capacity to advance shared military and security goals through its range of initiatives and regular military exercises, including the large-scale “Peace Mission” drills that involve all members, than the reformed Quad has been able to do thus far.

In its early years, concerned Western analysts described the SCO in somewhat breathless terms as a nascent Central Asian Warsaw Pact. While that was premature, as the leaders of eight member states prepare to gather near the tomb of Tamerlane the great, the geopolitical significance of the Central Asian space to the dynamics of world politics, the scale of the SCO’s membership, and its decidedly illiberal ambitions, mean that this body has to be taken seriously on its own terms and not just as a backdrop for a Putin-Xi meeting.