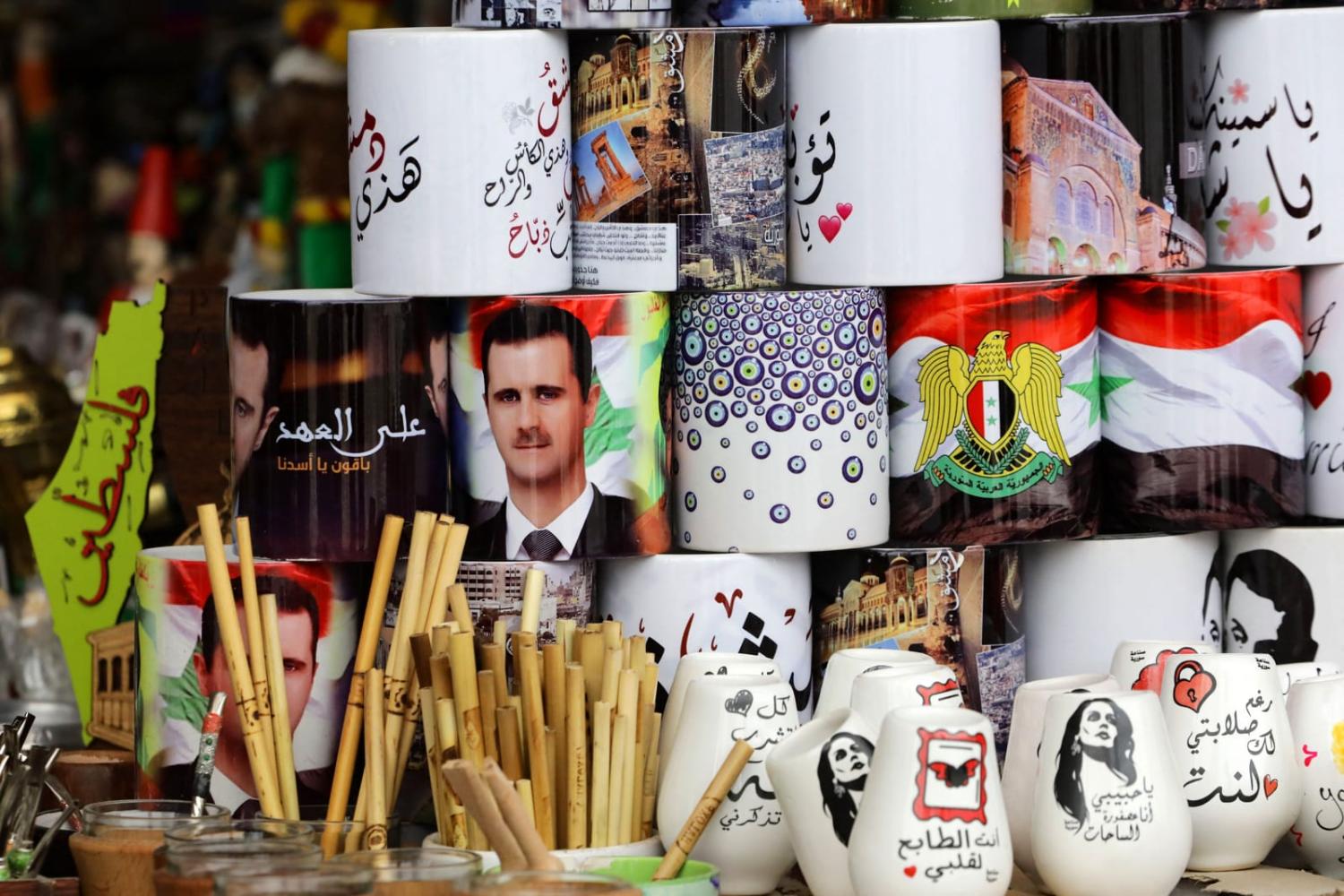

In May this year, leaders of the Arab world welcomed Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad back to the Arab League. Member states had ejected Syria in 2011, imposing economic sanctions and calling for an end to the targeting of civilians by the Assad regime. They now seem resigned to him sticking around.

Grasping the moment, Assad heralded “a new phase of Arab action for solidarity among us, for peace in our region, development and prosperity”. Although happy to be back in the Arab fold, he reserved the right to do as he pleases at home, stating, “It is important to leave internal affairs to the country’s people as they are best able to manage their own affairs”.

Syrian opposition activists and displaced persons responded to the rehabilitation of Assad by the Arab League with dismay, some characterising it as a “grand betrayal” of the Syrian people, given the 12 years of human rights abuses they have endured at Assad’s hand.

Despite his war crimes, the normalisation of Assad as part of the furniture in the Arab world seemed complete in November when he jetted into Saudi Arabia to attend an Arab summit on the unfolding crisis in Gaza.

This is not to say that normality has returned to Syria, however. Even if Assad is ensconced in the presidential palace, stability and peace remain unattainable for many Syrians.

With global attention turned towards Gaza and Ukraine, and no longer chastised by the Arab League, Assad gave himself a green light to bomb rebel-held Idlib in November, killing scores of civilians. In Syria’s northwest, this is the last remaining stronghold of opposition forces. Since November, the Syrian military, with backing from Russia, has targeted cities and towns across the region, home to more than four million people, in what the United Nations has described as “the largest escalation of hostilities in Syria in four years”.

Yet this show of force does not conceal the fact that Assad has limited control and authority over the territory of Syria. Iran has been a pillar of support for Assad since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, yet Islamic Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) stationed in the country have been targeted by Israel and more recently in airstrikes by the United States. In response, Iranian-aligned forces have stepped up attacks since November on international coalition bases in eastern Syria, an area outside of Assad’s control, while fighting continues in areas under the sway of Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Meanwhile, ISIS remains a thorn in the side of all actors in Syria’s northeast. In recent weeks it has carried out attacks against Syrian regime forces in Raqqah, against Iran-backed militias, and against the SDF in Deir Ez-Zour. This complex theatre of conflict has predictably negative impacts on the local civilian population.

Syria’s northeast has also seen a surge of Turkish attacks against the SDF, a key US partner in the battle against ISIS. Türkiye, which has made repeat incursions into northern Syria, deems the SDF a terrorist groups due to its links to the outlawed Kurdish Workers Party.

In October, following a PKK suicide bomb attack in Ankara, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan deemed all infrastructure and energy facilities within the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria, with which the SDF is affiliated, to be PKK infrastructure, therefore legitimate targets for Turkish weapons. Sure enough, with global attention elsewhere, Türkiye destroyed water and energy facilities in northeast Syria, also allegedly killing 11 civilians.

Further complicating the situation, tensions have escalated between Türkiye and the United States. In early October, the US military downed a Turkish drone that was targeting Kurdish infrastructure but strayed too close to a US base. Washington and Ankara remain allies, but Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan seemed to suggest the possibility of retaliation.

For their part, Syrian Kurds are wary of being dragged into a wider conflagration between the United States and Iran in Syria, while also dealing with challenges to their rule by local Arab communities that appear to be fomented by Iran and Assad.

In the south, closer to Assad’s power base, the climate is only marginally more stable. For several months, the Druze community in al Suwayda has been taking to the streets to peacefully call for political change, protests that have spread to Daraa, the site of the original uprising against Assad in 2011.

Thus, Assad may have been normalised to some degree by his return to the Arab League, but his legitimacy is challenged, his rule far from assured and disruptions to the lives of everyday Syrians continue unabated.