From the 1990s to the early 2000s, Oceanic writer and poet ‘Epeli Hau’ofa wrote of challenging the way the world (and even people of Oceania) often viewed Oceania with belittlement, due to both its geographical location and its mostly small populations. Fast forward to 2020, Oceanic feminist academic, Yvonne Te Ruki-Rangi-o-Tangaroa Underhill-Sem provided a more momentous challenge for the times by coining the term “audacity of the ocean” – a metaphor she used to describe the need to reconcile tensions between unequal relationships and provide a trajectory to move forward.

This message is particularly germane to ideas about development approaches and aid effectiveness. In other words, North domination, white supremacy and patriarchal colonialism should be unapologetically rejected. Underhill-Sem says not only do we need to reimagine our Ocean and reject notions of belittlement, but we also need to go much further and call out the tensions of unequal power relations in order to see meaningful change moving forward.

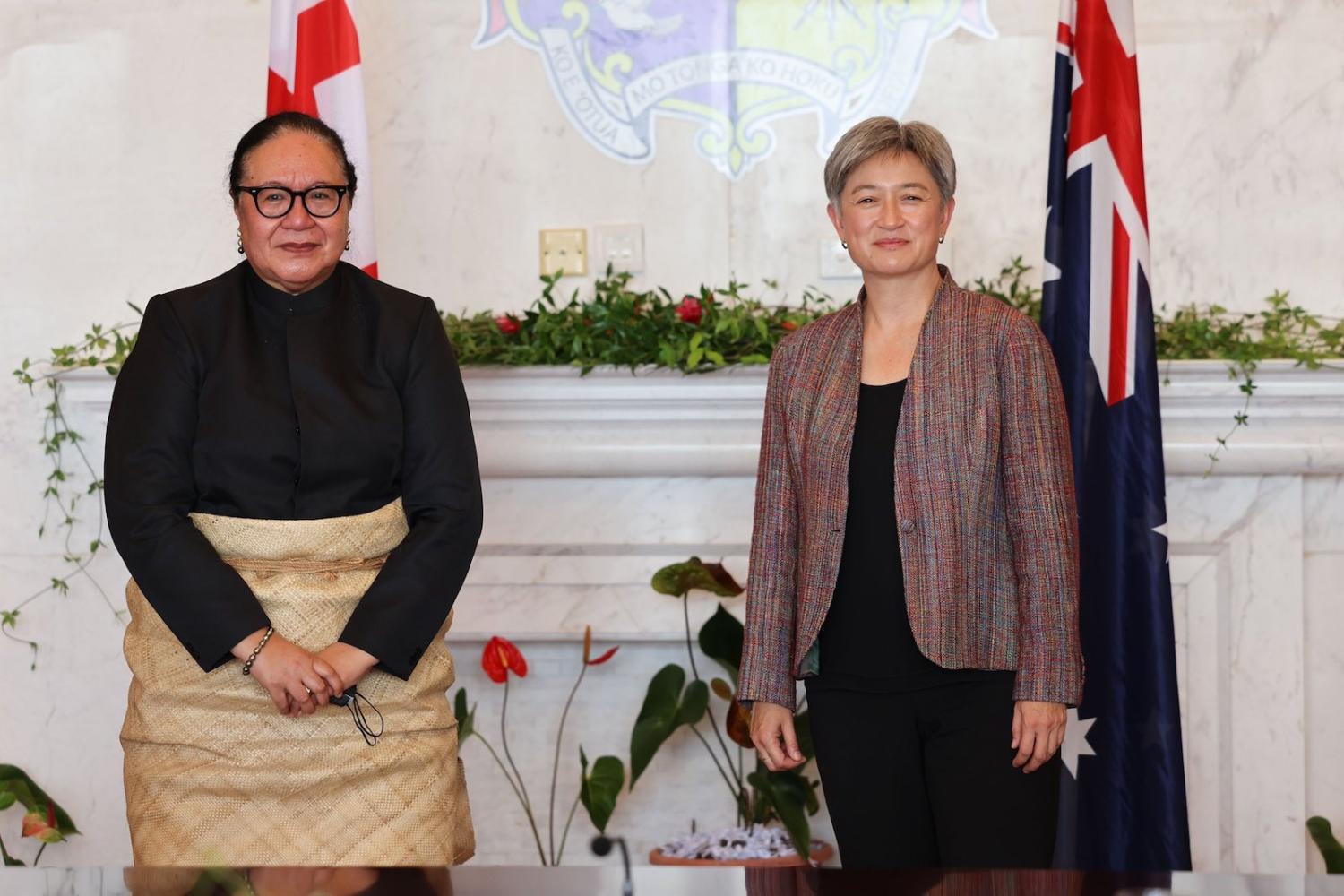

Penny Wong wants this. Australia’s new Foreign Minister is being an audacious ocean herself by breaking these unequal power dynamics down and welcoming the nurturing of the Vā (relationships).

There have been many conversations among women’s rights actors raising concerns about the undermining of their autonomy when it comes to aid, development and humanitarian planning.

“We will listen and we will hear you – your ideas about how we can face our shared challenges and achieve our shared aspirations together,” Wong declared on her first official visit to the Pacific. She went on to say that Australia would “draw on all elements of our relationships to achieve our shared interests”. This came soon after her commitment to a First Nations foreign policy for Australia.

For us in the Oceanic Pacific, building and nurturing relationships are paramount. We connect by understanding who we are, where our roots lie and the interconnectedness of our alliances. We story-tell our experiences, our knowledge and our visions for a better Oceanic Pacific for all. We engage in Talanoa so we can learn more about you, and you about us. This is the only way we can move forward together in an equal partnership with shared values, goals and visions.

For women’s rights organisations in the Oceanic Pacific, Wong’s words carry a lot of hope.

There have been many conversations among women’s rights actors raising concerns about the undermining of their autonomy when it comes to aid, development and humanitarian planning and design. Unequal partnerships at the onset give way to ongoing colonial practices and the partnership is almost always perceived as donor and beneficiary. The missing relationships often means the Global North lacks contextual knowledge of the real situation of women and girls in the Oceanic Pacific, resulting in unrealistic expectations and low confidence to negotiate on the part of the women’s rights organisations.

In 2020, I led research with the International Women’s Development Agency (IWDA), Creating Equitable South-North Partnerships: Nurturing the Vā and Voyaging the Audacious Ocean Together, which called for the reimagining of Global South-North relations. There is an even bolder call for Global North partners that want to work with women’s rights organisations in the Oceanic Pacific to develop feminist foreign policies, which will lead to improved relationships and valued partnerships.

I held courageous conversations with 35 women leaders across the Oceanic Pacific who have worked with Global North organisations over the past three decades. There was an overwhelming focus on the lack of nurturing relationships between South-North partnerships. It goes against what we in the Oceanic Pacific view as the most critical aspect of a partnership – the ability and desire to invest in the relationship and the spaces between. The disconnect was best explained by one of the women leaders:

You can sense it from the way they communicate and the things they care about which is always about numbers and tables and reports and ticking the box. It’s never really about our relationship with each other and making sure we learn from them and they learn from us.

Developing equitable partnerships and achieving empowered relationships, which Wong alludes to, were the main outcomes of the 2020 research.

I feel Wong’s audacity of the ocean, her sense of wanting to nurture the spaces between and to focus on the spaces that relate. I want to remain optimistic and hopeful that South-North Global partnerships such as Australia-Oceanic Pacific partnerships will set sail on a decolonised voyage that is built on mutual solidarity and understanding. This requires a massive paradigm shift from unequal colonial practices to one that places power and reimagining, co-design, co-creation, co-responsibility and co-accountability in both Australia and the Oceanic Pacific’s hands. Or as another women leader put it:

We are strong women. We need to speak up and tell them when things will not work for us and we should only partner with those who will listen to us.