The United Nations has overwhelmingly adopted a landmark resolution requesting an International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the obligations of states to act on climate change. It will be a non-binding opinion but holds moral authority and adds to the pressure on high emitters to take action.

For Pacific Island nations facing acute dangers from global warming, this latest move is decisive. “We’re not drowning, we are fighting,” Pacific youth climate warrior Brianna Fruean declared two years ago, and put the challenge directly to world leaders. “The real question is whether you have the political will to do the right thing.”

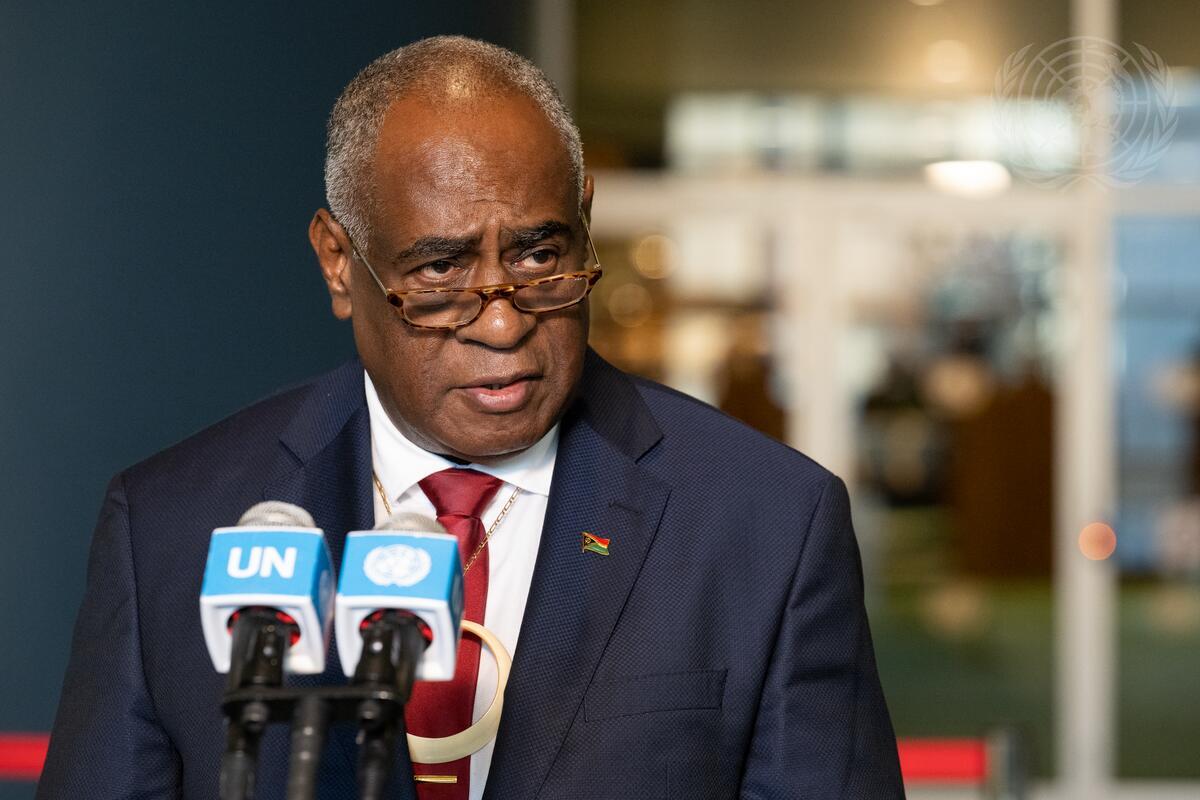

Fruean’s question hangs in the air – will the world do the right thing? With the United States recently approving a massive new oil project in Alaska, it’s hard to be optimistic. Australia has invested hundreds of millions into Pacific adaptation, but more investment from the global community is required. Vanuatu alone estimates it will require US$1.2 billion by 2030 to build climate resilience. Vanuatu led the drive to request the ICJ advisory opinion.

The latest International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report suggests doing the right thing and acting on climate change is not coming easy. It warns the world is unlikely to meet the Paris Agreement commitment to limit the temperature increase to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. The Pacific islands’ request to keep warming to 1.5°C to “stay alive” is slipping from our grasp. Adaptation planning and implementation has progressed, but current institutional and financial arrangements are holding us back.

“Vulnerable communities who have historically contributed the least to current climate change are disproportionately affected”, the IPCC report warns. Translated, that means Vanuatu, recently hit by two category 4 cyclones affecting more than 80 per cent of its population, is likely to experience even more severe and frequent events – they (like others) won’t recover from one event before the next one hits.

When the highest ground in countries such as Kiribati and Tuvalu is less than a few metres above sea level, an extreme weather event can trigger multiple and cascading crises related to water, food, shelter and economic security. Livelihoods are at stake, too. Between 50–70 per cent of Pacific people depend on agriculture and fishing for their incomes and food. The increasing coral reef losses, tuna fisheries decline, and intense droughts will affect poverty levels and ecosystem health in the neighbourhood. For largely subsistent economies with vulnerable supply chains, that’s seriously concerning.

In economics, efficiency requires that the polluter pays – so far, polluters aren’t paying for climate impacts. Market mechanisms are failing. Uncosted impacts are not being accounted for. Pacific Islanders struggle to access adaptation funds – the promised climate fund of $100 billion per annum is falling short, and loss and damage funds are still just being discussed. Speaking to The Guardian, Samoan Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mata‘afa despaired: “There are already examples in the Pacific of communities, whole communities, that have relocated to different countries. They’re really having to address issues of sovereignty through loss of land.”

There is a glimpse of light in the latest IPCC report for the Pacific Islands. It makes clear that what they have been asking for over the last couple of decades is now officially, scientifically recognised as the right way forward.

First, and most obvious, the world needs to mitigate and drastically reduce carbon emissions, full stop.

However, even if we supercharge mitigation, climate impacts for small and vulnerable islands will still be severe. Some trends are now baked into the global ecosystems.

On adaptation, step one is to ramp up adaptation funds and ensure that the most vulnerable can access the finances they need. This will require targeted adaptation funds with simplified access processes. The report notes progress, but gaps persist and will continue to grow if the world sticks to “business as usual”. Put simply, effective adaptation in the Pacific Islands is being held back by institutional shortcomings.

Second, invest in adaptation options that make a difference. The IPCC report has plenty of suggestions, some of the most relevant to the Pacific are targeted support for cultivar (crop) improvements to boost resilience and food security in the face of climate change. Others include community-based adaptation to develop place-specific solutions integrating diverse knowledge (indigenous, cultural and scientific), climate-proofing infrastructure, better early warning systems, and systemic social protection mechanisms for rapid recovery. The latter is lacking in the Pacific Islands. There are many more suggestions, but underlying these are the need for genuine partnerships, support for local systems (not parallel systems) and community embedded science.

We are not starting from scratch, there are successes on which to build. The locally led Pacific Humanitarian Pathway, the inclusive Australian Humanitarian Partnership, the locally adapted UN Cluster System, and the strengthened and empowered National Disaster Management organisations all provide sound foundations. The Pacific Islands Forum is proposing a locally focused and managed Pacific Resilience Facility to invest in community resilience – to date, not well supported.

All this illustrates that there has been more than enough hand-wringing and interest protection. The IPCC report is clear: “There is sufficient global capital and liquidity to close global investment gaps, given the size of the global financial system.” The latest big spends on AUKUS and the Ukraine-Russia war show capital mobilisation is possible when there is the will to act. Climate action is critical if we are to limit the human and ecological crises unfolding.

Echoing numerous regional declarations from the Pacific Islands, the IPCC report notes the world needs a coordinated effort to accelerate climate action. In short, the message is: time’s up, and if we don’t act, we all lose. Some will pay a higher price, sooner. The cost to Pacific people will be more lives, livelihoods and even countries. The world has an obligation to ensure that doesn’t happen.