It was only last year Scott Morrison marched with a baseball cap and Daggy Dad political persona to a triumphant victory in a seemingly unwinnable election. “How good is Australia! How good are Australians!” was the ScoMo catchcry.

Which makes his apparent transformation into a serious scholar of international relations theory all the more remarkable.

“We can make our world more Grotian and less Hobbesian,” the PM soothed in an overnight speech to a British audience at the Policy Exchange think tank.

Sceptics will wonder if Morrison is simply giving himself a clever political makeover by exploring the epistemological foundations of modern statecraft.

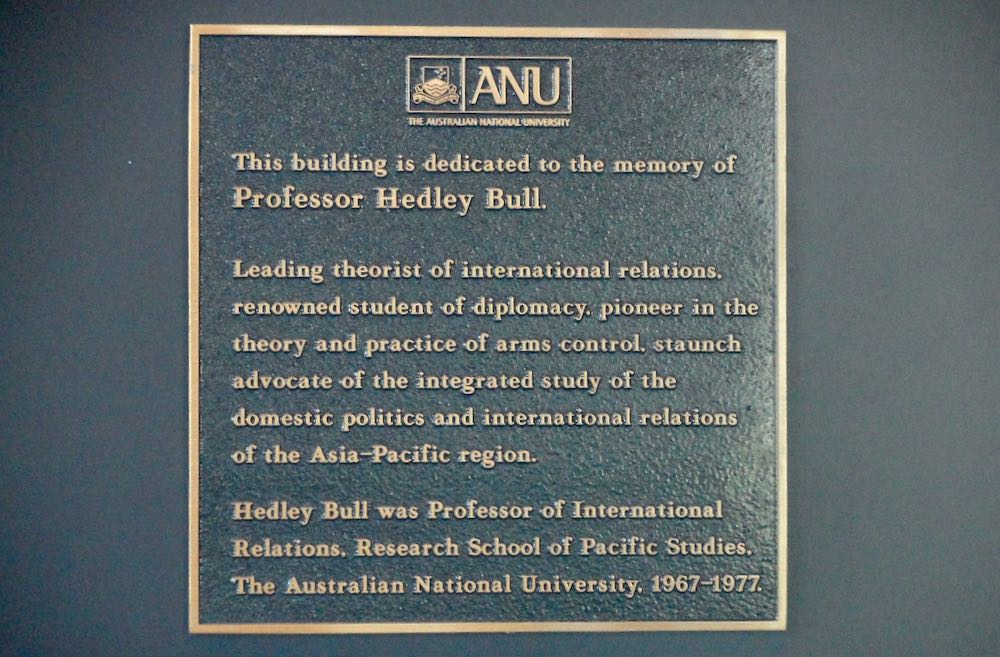

Morrison is making a habit of citing famed Australian international relations academic Hedley Bull to present a big-picture vision of the world in Covid times, underscored, as it is, by accelerating strategic competition. In August, Morrison invoked Bull’s concept of “international society”, which drew heavily on 17th-century Dutch thinker Hugo Grotius’s ideas, to declare “China and the United States have a special responsibility to uphold what Bull described as ‘the common set of rules’”. Morrison again noted Bull’s focus on international society in his Policy Exchange lecture.

It’s always tricky to quote selectively from a broad body of writing as if to capture the essence of an author’s attitude. Bull, who died in 1985, is central to what is often referred to as an “English school” of international relations theory, and his own struggle to reconcile notions of order and justice has inspired voluminous contemporary scholarship of its own.

But in Morrison’s philosophical musing, he might ponder one of Bull’s more explicit warnings delivered in the 1983 Hagey lectures. Bull’s lectures explored Hobbes, Grotius, the rights of sovereignty and the demands of developing nations no longer supplicant to the established powers – all emerging into a sense of a “world common good”. As Bull put it:

Particular states or groups of states that set themselves up as the authoritative judges of the world common good, in disregard of the views of others, are in fact a menace to international order.

In this era, such a menace is the focus of China critics, who rightly point to Beijing’s false claims as head of a vanguard of developing nations. But Morrison’s rallying cry “for concerted leadership and action by like-minded liberal democracies” to secure peace and stability would seemingly have won little sympathy from Bull. As Bull went on to warn:

States are notoriously self-serving in their policies, and rightly suspected when they purport to act on behalf of the international community as a whole.

In other words, Bull was ecumenical in his scepticism whenever “national interests” were involved, no matter the character of the government. The challenge he saw was to “seek as wide a consensus as possible” but act as local agents of a world common good.

None of which contradicts the Morrison vision, but the PM will need to do more real-world explaining of shared policy challenges, in particular climate change, to win over other countries to what he called a “judicious balance of the Hobbesian, Kantian and Grotian traditions”. As he admitted on climate policy, “emissions, they don’t have accents, they don’t have languages or nationalities”.

Sceptics will wonder if Morrison, the man derisively dubbed “Scotty from Marketing” by opponents at home for his background in public relations and gift for spin-doctored lines, is simply giving himself a clever political makeover by exploring the epistemological foundations of modern statecraft.

Personally, I’m not going to fault the effort, much as it takes me back to an earlier life working as a university tutor. Morrison’s political career has been in many ways defined by a focus on “sovereignty” – whether in stopping the passage of asylum-seeker boats or more recently railing against “negative globalism”.

Much as sovereignty is presented as permanent and solid, it’s an abstract construction, so the theory behind it is important to understand and acknowledge.

But more so, Morrison needs to explain and resolve his preference that Australia not be forced into any “binary choices”. He argues modern economic interdependence makes the geopolitical contest of the present “even more complex than those during the Cold War”.

Yet even before the rise of China, globalisation has always carried a democratic deficit that leaders have struggled to reconcile: how to maintain meaningful policy control while still allowing citizens to make decisions. None of this fits into a simple slogan.