China was expected to be furious about the recently signed AUKUS security pact. After all, it is generally believed that the deal to provide Australia with technology to build nuclear submarines and the associated cooperation with the United States and United Kingdom amounts to a significant security pact to contain China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region.

But China in truth responded to the pact moderately. That sort of behaviour that might be ordinarily assumed to be on display by an angry China did not occur.

Beijing has so far responded chiefly with words rather than deeds. At the regular press conference on 16 September, the day of the AUKUS announcement, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said “nuclear submarine cooperation between the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia has seriously undermined regional peace and stability, intensified the arms race and undermined international non-proliferation efforts”. Condemnation, indeed, but hardly fire and fury.

On 29 September, in phone conversations with his Malaysian and Bruneian counterparts, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi reiterated that the AUKUS arrangement “may trigger the risk of nuclear proliferation, induce a new round of arms race, and undermine regional prosperity and stability”. Beijing made its comments on AUKUS with disapproval and suspicion, but it cannot veto or disintegrate the pact. Nor did Beijing move to impose any kind of sanctions on the three AUKUS countries following the launch.

The message was that the US needed to repair the damaged relations first before seeking feasible cooperation with China.

The diplomatic language amounted to a mild rebuke. Beijing’s wrath is usually expressed through much stronger phrases, highly charged with paranoia. For example, in response to the South China Sea arbitration case initiated by the Philippines in 2013, Beijing issued a series of position papers, one of which stated that “[t]he unilateral initiation of arbitration by the Philippines is out of bad faith. It aims not to resolve the relevant disputes between China and the Philippines…but to deny China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea.” China’s outrage was clear. Beijing completely rejected the arbitration and accused the Philippines of sabotaging China’s claims in the South China Sea.

So why did Beijing respond to the launch of AUKUS with relative self-control and restraint? Has the AUKUS deal successfully blunted China’s assertiveness? Or is there some other explanation?

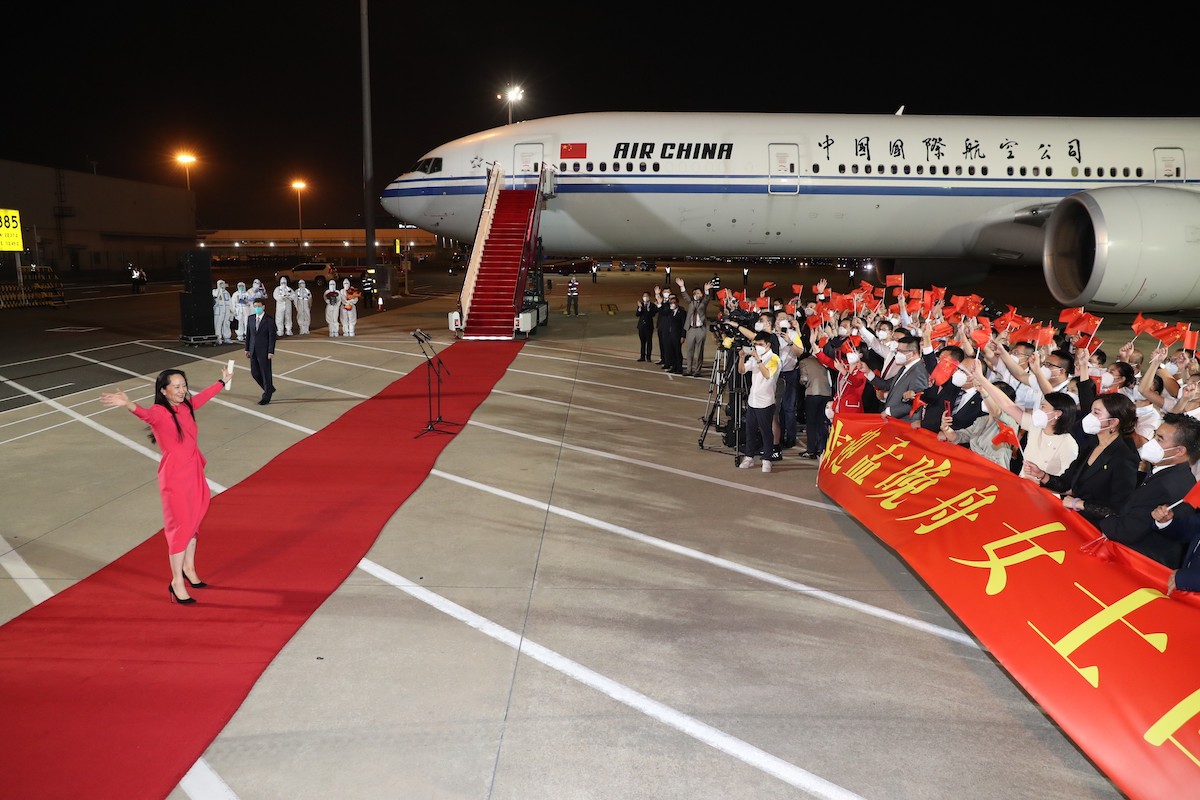

Some clues might be found in another high-profile case unfolding around the same time. Barely a week after the AUKUS launch, Meng Wanzhou’s return to China swamped the news. The CFO of Chinese tech giant Huawei had been arrested and detained in Canada from December 2018 at the request of the United States over fraud charges of circumventing US sanctions against Iran. On 24 September this year, she was freed and boarded a flight chartered by the Chinese government for China under a deferred prosecution agreement, in which the US Department of Justice agreed to dismiss the fraud charges in December 2022 on condition of her compliance with certain rules, including not to further challenge the factual allegations made by the US government.

Meng’s case has been a barometer for US-China relations, which deteriorated rapidly during Donald Trump’s presidency. During a July 2021 meeting in Chinese port city Tianjin between senior diplomats from both countries, the Chinese side handed two lists to the US officials for consideration: one a “List of US Wrongdoings that Must Stop” and the other a “List of Key Individual Cases that China Has Concerns with.” In the first, China urged the Biden administration to reverse the hard-line policies towards China implemented by his predecessor, including by dropping the pursuit of Meng.

It seems likely that the United States has been seeking China’s cooperation and the decision relating to Meng was a goodwill gesture.

In China, Meng’s release has been seen as a diplomatic victory for Beijing. It implies that the United States has given due consideration to the two lists and that there can be a turning point in bilateral relations, despite the continuing rivalry between the two powers.

It seems likely that the United States has been seeking China’s cooperation and the decision relating to Meng was a goodwill gesture. On 1 September, for example, US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and Wang Yi held an online meeting to discuss climate change, reportedly in a bid to solicit a further commitment from Chinese leaders to curb the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Wang responded with a metaphor that while the United States wanted cooperation on climate change to be an “oasis” in the bilateral relations, “if the oasis is all surrounded by deserts, then sooner or later the ‘oasis’ will be desertified.” The message was that the United States needed to repair the damaged relations first before seeking feasible cooperation with China.

So with Washington about to extend an olive branch by dropping the pursuit of Meng, Beijing knew that it would be inappropriate to react aggressively to the launch of AUKUS. Meng returned to China about ten days after the three-way partnership centred on the nuclear submarines was launched. It must have taken some time for the United States and China to organise Meng’s release and return – arrangements that seem unlikely to be accomplished in just ten days – suggesting an improvement in US-China ties occurred before the launch of AUKUS. It also seems reasonable to conclude that the changing atmosphere between the United States and China had an effect on China’s response to AUKUS.

What’s the implication then? It means that should US-China relations cycle to another low point, China may yet respond to AUKUS tensely. China is a pragmatic actor. Beijing tends to continuously adjust its (re)actions in accordance with changes in circumstances.